Good Design?

I’m given to thinking a great deal about design because it is such a black art for me. Engineering I can get a handle on because it is objectively based in science (it also happens to be what I am schooled in). Even if I do not understand the exact calculus behind the theory, I do at least understand the theory. Given the same set of variables two people will come up with the same solution—there are defined mathematical laws to guide you. What makes a car look good is a completely different matter because what makes a shape so pleasing is mostly indefinable. It’s easy to say what one likes and dislikes, but it’s hard to convince those around you that may disagree that you are more correct than they are by pointing to a calculation.

Having said that, I have some personal theories as to what I like when it comes to car design. Good automotive design in my mind’s eye comes down to a few elements. It should be based on the mechanical configuration of the vehicle and work in concert with the mission of the car. The surface development should be clean but not necessarily simple. And finally, the proportion and stance should be natural.

There you go, that’s why design intrigues me as much as it infuriates me—not one of my “elements of style” are definable by anything other than subjective impulses.

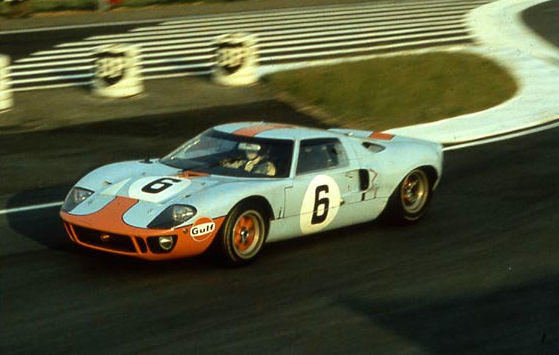

My first element is rooted in the “form follows function” idea of design. Some of the best looking vehicles are race cars and in particular the Ford GT40 of the late 1960’s. Every surface detail is beholden to the mechanicals underneath as well as the need to cheat the wind. It’s a give and take between the wind and the hard points of the car—which brings about a certain tension in the design that even wide eyed children instinctively find exciting. Thanks to the level of aerodynamic understanding and technology at the time, many of the elements of the GT40 had to be filled in by human thought rather than computerized modeling. I think the GT40 was created at a time when the balance between science and art was just about perfect in terms of design.

I’m not a fan of superfluous wings, fender bulges, and air scoops unless they are needed to better the performance of the vehicle. Truly great designs can meet the needs of the engineering department without such add-ons by incorporating them in the design right from the start. The surface development of a car, the way the skin twists and turns over the mechanical skeleton, is a complex symphony of curves, flats and creases. Shadows and light play off of the surface to give the design more depth and the viewer even more satisfaction if done with a certain bit of economy. The BMW 1 Series is a perfect example of way too much surface modeling on such a small car. With concave and convex curves punctuated by sweeping creases, the 1 Series surface is much to busy. The MINI is quite the opposite in its surface detailing allowing the shape and stance of the car to define its presence more than undulating sheet metal.

Proportions and stance are both the biggest contributors to good design and the toughest to get right thanks to modern packaging concerns. The layout of the engine and suspension is often dictated by engineering, and the interior by marketing (as well as the consumer). Government safety regulations add another dimension to the picture. The size of the cabin and the basic proportion of the car are thus foisted upon the designer by outside influences. To make it work to the advantage of the design much thought and time is therefore required. The key to making it work for me is the way the car body sits on its suspension. The location of the wheels relative to the rest of the body helps define the attitude of the car. Sports cars tend to get it right more often thanks to the fewer compromises they have to make to packaging concerns, but there are a few sedans that can pull it off. BMWs do it better than most, as does Jaguar with its XJ sedan line.

At the end of the day one cannot get around the fact that good design is subjective-- as my pitiful attempt to objectify some of what I consider core elements proves. But I’ll keep thinking about it and if I come up with any better ideas, I’ll let you know.